Prepared by Chris Aulich, October 29, 2014

This article addresses the performance of three Australian airports since they were privatised by divestment. They represent cases of divestment in a monopoly environment, with ownership arrangements for each airport varying markedly. The performances of the divested airports are considered using both financial and non-financial data. There are significant implications for future divestment policies, including the value of divestment as a policy response of governments in less competitive environments, the use of particular infrastructure investment models, and the nature of the linkage between ownership structure and financial performance.

1. Introduction

The Federal Airports Corporation (FAC) was established in 1987 as a government business enterprise (GBE) to operate airports on behalf of the Australian government. By 1997, the FAC managed 22 airports, but in that year the national government announced that airports would be privatised by way of divestment. This article addresses the performance of Australia’s three largest airports since divestment and seeks an answer to the question of whether this divestment has enhanced performance and created value for government, shareholders and transportation users.

2. Divestment Policies and the Australian Context

Differences in performance between public and private organizations seem to depend less on ownership and more on other factors such as size, task and technology. For example, government-owned hospitals resemble private hospitals more than government-owned utilities (Rainey, 2009). This broad conclusion about ownership and performance is supported by many other researchers (for example, Lane, 1993), yet the notion persists that somehow a simple change in ownership, public to private, will in itself enhance organizational performance.

The notion of competition as a more significant dimension of performance underpinned divestment policies pursued by the Australian Labor government in the 1980s and 90s. In bringing to an end Australia’s longstanding preference for public enterprise in areas such as banking, airlines, public utilities and telecommunications, Labor adopted a pragmatic policy in determining which enterprises would be privatised: enterprises in monopoly markets such as airports, or those which had significant community service obligations such as Australia Post and Telecom, remained in government ownership, while public enterprises in competitive markets such as the Commonwealth Bank and Qantas were divested. Ownership, public or private, was not the primary goal of divestment policies; rather it was the need to ensure competitive environments as well as protecting the public interest involved (Aulich & O’Flynn, 2007).

By contrast, the election of the Liberal-National Coalition government in 1996 brought with it a different strategy, which is best seen as systemic or political (Aulich & O’Flynn, 2007). Prime Minister Howard (1981, 1995) had earlier argued that individuals rather than government were inherently better at making decisions about their future, and he was “profoundly suspicious” of what governments could achieve arguing that governments control, while the private sector provides enterprise.

Consistent with these views, the Howard government accelerated the pace and scope of privatisation, especially through divestment of public enterprises. The core principle of the Howard government’s approach was captured in a speech by the Minister responsible for the public sector. In this speech, he argued that the government took a “Yellow Pages” approach to public enterprise – if such services existed in the Yellow Pages telephone directory there was no reason why they should be provided by government (Kemp, 1997). The Howard government accrued $A61 billion from divestment of public enterprises between 1996 and 2008 (di Marco, Pirie, & Au-Yeung, 2009) when Australia undertook the largest disposal of assets in its history. These divestments included the sale of most of the nation’s main airports in the period from 1996 to 2003.

Airport divestment was initiated in 1997 with the sale of Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth Airports, followed by the sale of Adelaide, Canberra and Gold Coast Airports, the remaining smaller airports in 1998, Sydney Airport in 2002, and the Sydney Basin Airports of Bankstown, Camden and Hoxton Park in 2003. The divestments were undertaken by direct trade sale with various private consortiums bidding for the right to receive a long-term lease over each airport.

The decision to divest Australia’s airports was influenced by a complex set of factors, both pragmatic and systemic. The government argued that the sales would increase economic efficiency in the provision of aviation services, including investment and pricing reforms and removal of cross-subsidies among airports. Sales would improve managerial efficiency and flexibility at Australia’s airports to reduce costs and increase global competitiveness of the Australian aviation industry and its users. It would also enable government to avoid the large capital investments required by airports and make resources available for other public programs in the belief that the private financial market was capable of funding major transport and infrastructure investments and had the appetite for that investment. Finally, it would reduce disincentives to the deployment of new technology and working practices in airport management and operation (TFF Australia, 2007).

For some in government, the private sector would operate the airports more efficiently, in spite of the monopoly arrangements that would be created in each state. Prime Minister Howard (2002) argued that “we think it better for private organisations to run airports with governments regulating safety and air traffic control … I mean there are good … economic reasons for those airports to be operated by private industry”. In short, the view was taken by the then government that changes in ownership would deliver improved performance.

Since privatisation, these assertions about ownership and performance have not been tested in Australia. More widely, there has been some research which points to the fact that privately-operated airports in Latin America have not outperformed publicly operated ones (Perelman & Serebrisky, 2010) and that changes in productivity were largely due to adapting well known technologies and production processes. Vogel (2006) concluded that public airports may better be able to capitalise on their government backing, giving them greater ability to assume higher leverage in the financing of productive assets. By contrast, Oum, Yan and Yu (2008) found that average efficiency of an airport is higher when owned by the private sector and that airports with mixed ownership were less efficient than those operated solely by the public or private sectors. The TTF Report, which was industry-sponsored, unsurprisingly concluded that, “taken collectively, this study finds that the [Australian] government’s privatisation objectives have been achieved” (TFF, 2007: 4).

In one of few robust analyses of Australian airports prior to divestment, Abbott and Wu (2002) concluded that airports recorded strong growth in technological change and total factor productivity, but did not fare all that well in terms of growth in technical and scale efficiency during the 1990s. At the international level it appeared that Australia’s largest airports fared reasonably well in comparison to airports overseas, although they still possessed the potential to realise further gains. Assaf (2011) concluded that most Australian airports have experienced significant total factor productivity increase since privatisation while few airports have recorded productivity and efficiency decline over the same period. The analysis suggests that this productivity increase has been the result of changes in pure and scale efficiencies. However, the Assaf study relied on three output indicators (the number of passengers, total cargo and number of aircraft movements) and three input indicators (total number of staff employed, total airport area and operational costs), and did not consider user and customer perceptions of service standards, nor did it account for the effective monopoly environment which is likely to have impacted on some of the indicators, in the absence of effective competition in each major city.

3. Ownership and Financial Performance

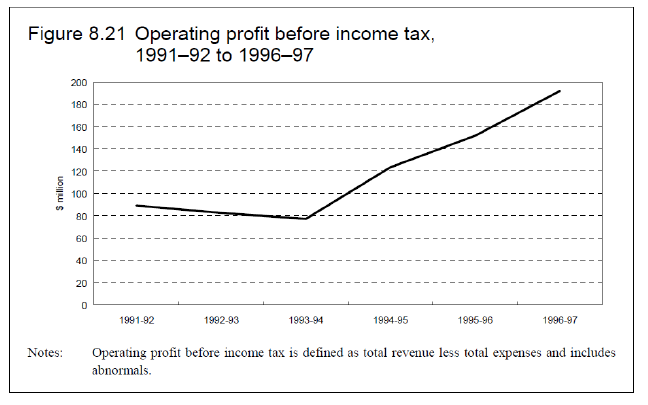

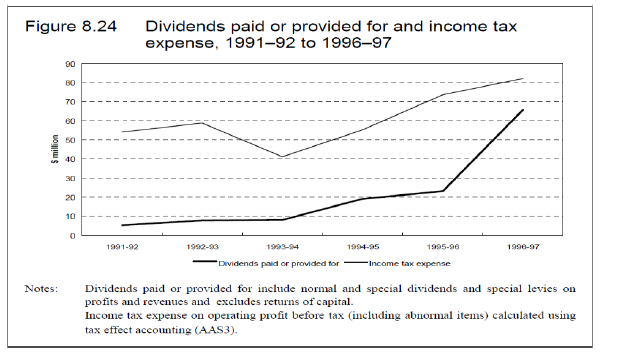

The ideal is to compare the performance of the individual airports before and after they were divested. Unfortunately, comparative figures were only available for Sydney airport. The Productivity Commission’s (PC) report (1998)2 on the performance of GBEs, including all airports controlled by the FAC, provides a useful metric by which to assess financial outcomes since privatisation. This report only presents aggregated data for all airports it operated, but the data can be used as a comparator. The aggregate figures are strongly affected by the performance of the three largest airports, Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, as they represented 81% of the FAC’s profits for the year ended 1997 (PC, 1998: 337).

The PC report (1998) indicates that the FAC was able to liberate considerable wealth for the government through its period of stewardship. For example, profits before income tax doubled in the six years the FAC operated the airports (Figure 1). Figure 2 indicates that the airports made ongoing positive contributions to the government’s revenue base through income tax and dividend receipts. Of note was the Productivity Commission’s report that in 1997 the government assumed approximately three quarters of a billion dollars in debt the FAC had been servicing in order to improve the attractiveness of the airports to potential bidders when divestments were initiated.

Figure 1. Federal Airports Corporation (FAC): Operating Profit before Income Tax

Figure 2. Federal Airports Corporation (FAC): Dividends Paid or Provided For and Income Tax Expense

- Financial Performance of Sydney Airport

In June 2002 the Southern Cross Airports Consortium won the bidding process for the sale of Sydney’s Kingsford Smith airport (Sydney airport). The consortium paid approximately AUD$5.6b for a 50-year lease with an option to renew for a further 49 years (APH, 2006). The price paid by the consortium represented a multiple of 14.3 times EBITDA (i.e. earnings before income tax, depreciation and amortisation). The sale transaction was completed in June 2002, at which time Sydney Airport Corporation Limited (SACL) was acquired by Southern Cross Airports Corporation Pty Ltd. (SCAC). SCAC is the parent company and Southern Cross Airports Corporation Holding Limited (SCACH) is the ultimate parent company of SACL (SACL, 2003).

At the time of sale, the major shareholder in the consortium was Macquarie Airports (MAp), with 63% of the equity. The remaining members of the consortium were infrastructure specialists such as Ferrovial Aeropuertos and HOCHTIEF AirPort, as well as the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan Board. MAp was the primary owner and manager of Sydney airport in its early years of private ownership.

The aggregate aeronautical revenues reported by Sydney airport in its general purpose financial reports (GPFR) since privatisation (except for the period 2005 to 2007 for which figures are not available) shows that there was a steady year-on-year growth in this revenue stream 2002-2013, and that over the entire period aeronautical revenues grew by 158% while passenger numbers grew more modestly, at 59%, and aircraft movements by 28%.

Data reveal that from the first year of privatisation the airport owners did not pay income tax until 2013. In 2003 it paid $33m in tax, but given that the company made a loss of $256m in that year, it appears the tax paid in that year related to operations the year before, when it was government-owned. Following a tax audit in 2012 relating to the 2010 and 2011 years, Sydney airport agreed to pay $69m to the Australian Taxation Office in 2013 (Sydney Airport Annual Report, 2013: 44).

Data to 2010 also indicate that Sydney airport has only been able to report an operating profit in one year since it was privatised, accumulating losses of approximately $2.2 billion. Reported retained losses would have been greater, except that Sydney airport was able to reduce its accumulated losses in 2006 with the introduction of International Accounting Standards. This introduction affected the balances in various accounts, resulting in a reduction of the accumulated losses that year of approximately $440m. It is perhaps surprising that in the same period as incurring such large losses, the airport chose to pay $798m in dividends to its owners.

The corporate structure of Sydney airport continues to be complex. Sydney airport is now a security traded on the stock exchange. From December 2013 the security was simplified to become a “stapled” structure including a trust (SAT1) and Sydney Airports Limited (SAL). SAL owns the various operating companies including SCACH, SACL and SCAC. Macquarie Bank moved away from its ownership role at about the same time, distributing to its own shareholders the securities in Sydney airport.

Prior to December 2013, there were two trusts, SAT1 and SAT2, and part ownership of other airports. The complexity is indicated by one excerpt from the 2012 Annual Report:

Net Operating Receipts provides a proxy for cash flow available to pay ASX-listed Sydney Airport distributions. The first table reconciles the Southern Cross Airports Corporation Holdings Limited (SCACH) (a subsidiary of SAT1 and SAT2) statutory result to its distributions declared. The second table incorporates ASX-listed Sydney Airport cash flows to determine total cash available to investors. Non-IFRS financial information below has not been audited by the external auditor, but has been sourced from the financial reports.

These annual reports also stated that the ASX-listed Sydney Airport had an 84.8% interest in SCACH in December 2012, but only a 79.4% interest at December 2011. In these circumstances, attempting to extend the detailed comparison is not likely to be useful. A brief review of the available financial information indicates that the airport has in recent years earned significant income for the group as a whole, for example it has continued to pay significant dividends and it enjoys a significant net return per passenger (ACCC, 2014).

The major components of operating cash flows and the net cash from operations indicate that Sydney airport has been able to generate positive and generally increasing net operating cash flows since 2006. Over the eleven-year period since Sydney airport has been privatised, the growth rate for cash received from customers has increased by a factor of about two and a half. This increase in cash receipts represents a combination of increased charges per passenger and aircraft movements, as well as increased rents for retail outlets and car parking. It was clear that Sydney airport’s average prices (excluding government mandated security) increased significantly in the period since privatisation (ACCC, 2011b: 47; ACCC 2014).

The company continues to incur considerable borrowing costs and this outflow is expected to continue for some time. The 2003 annual report indicates that the buyers of Sydney airport hold their interests through stapled securities, each being composed of a $50 ordinary share, entitled to dividends, and a redeemable preference share that earns interest at 13.5% per annum.

There has been a significant change in the relative proportion of Sydney airport’s liabilities compared to their asset. In 2001 and 2002, the airport reported positive net assets, that is, it had more assets than liabilities. The substantial increase in assets in 2003 is largely due to a revaluation of assets, rather than the purchase of new assets. This revaluation was driven by an accounting rule that required the assets to be reported at fair value by the buyer. The revaluation increased the carrying amount of the assets by approximately $2b. However, since 2003 there has been a substantial increase in liabilities, which have risen from approximately $1.4b to $8.1b by 2010 and to $9.2b by 2013. The majority of this increase has been due to external borrowings, and not from revaluations of liabilities. In the first year after privatisation, the debt rose from $1.3b to $6.1b, indicating the new financing arrangements and that the interest on this large debt meant that the airport entity fell into deficit.

The net impact of this increase in debt is that the company’s net assets fell from approximately $1.9b in 2002 to negative $960m in 2010, a fall of approximately $2.9b over a 9-year period. As noted, there has been further restructuring since 2010; combined net assets of the two entities of the stapled entity (SAL and SAT1) were recorded at the end of 2013 as $3.7b (assets of $12.9b, liabilities of $9.2b). This is a major reversal since 2010, but the real significance of this (that is, after disentangling the restructure) is difficult to determine.

This analysis challenges the notion that simply privatising a monopoly will inevitably lead to financial performance improvement. The financial reports indicate that since being privatised, Sydney airport has not been able to generate meaningful profits, despite doubling the amount of cash collected from customers. The well-designed equity instruments used by the new owners of Sydney airport provides an interest revenue stream of 13.5%, plus dividends. In addition, MAp was paid managerial fees, based on the value of the assets under management, rather than the net assets under management. This might partially explain the high increases in the debt levels reported.

- Financial Performance of Melbourne Airport

As with Sydney airport, Melbourne’s lease was opened for bids by public tender. The successful bidder for Melbourne was Australia Pacific Airports (APAC), a privately owned company that paid $1.3b for a 50-year lease in 1997 with an option for a further 49 years. At the time of acquisition, the major investors in this entity were the British Airports Authority, AMP, Morgan Grenfall Australia, and Hastings Funds Management. The current ownership structure also includes Australia’s government-owned Future Fund (16.8%) (Melbourne Airport, 2009).

Aeronautical performance data reported by Melbourne Airport in its GPFR show that there has been steady year-on-year growth in this revenue stream over the period surveyed and that over the entire period 1997-2013, aeronautical revenues grew by 344% while passenger numbers grew more modestly at 119% and aircraft movements by 41%.

Like Sydney airport, Melbourne did not pay tax for a number of years after privatisation. Analysis of previous year GPFR (untabulated) indicate that Melbourne commenced paying income tax nine years after being privatised. The 1997-98 GPFR for Melbourne airport reveals that the company inherited accumulated losses of approximately $8.5m. It took seven years to reverse this and produce accumulated profits. From 2005 to 2010 this balance has increased to $530m and the company has paid $647m in dividends. In the three subsequent years to 2013, net profits were $575m, while dividends were a total of $1,447.1m.

A small part of the difference in performance between Melbourne and Sydney can be explained by an accounting choice. Under the international accounting regime adopted by Australia in 2005, increases in the fair value of investment properties can be recorded in the income statement. Melbourne implemented this rule in 2007 and from the period 2007 to 2010 this has increased Melbourne’s retained earnings by $77m, and by a further $120m from 2010 to 2013. Sydney airport did not adopt this accounting choice.

Melbourne airport has generated positive net cash from operations in every year since privatisation. Borrowing costs are much lower than Sydney airport due to the lower debt burden and the lower costs of debt, approximately 8% for Melbourne against 13.5% for a large part of Sydney’s debt. The assets of Melbourne airport have consistently exceeded its liabilities and this is trending in a favourable direction. Some of the increase in assets is due to revaluations of investment properties, but this generally is of a minor nature. For example, in 2006, the revaluation increment on investment properties was $91m and the company reported total assets of $1,609m. This represents approximately 5.5% of total assets. In 2013, the equivalent figures were $44m and $3.4b, about 1.3%.

The performance of Melbourne airport stands in stark contrast to that of Sydney airport. While Sydney airport has been privatised for a shorter period of time, in the seven years since it has been privatised its retained losses increased monotonically to exceed $2.2b. From 2011 to 2013, however, Melbourne has commenced to make profits, totalling $287m over those three years. In addition, Melbourne has displayed better control over its debt levels and the cost of financing that debt.

- Financial Performance of Brisbane Airport

Brisbane Airport Corporation (BAC) paid $1.4b in 1997 to acquire Brisbane airport on the same 50+49 year lease arrangements that applied to both Sydney and Melbourne’s airports. The ownership structure of BAC on the date of acquisition was quite different from that of Melbourne and Sydney airports, as various national, state and local government entities held substantial interests in the airport. In 1998 the national government owned 27% of the firm’s shares through two commercial investing entities; the state government of Queensland owned 37% and the City of Brisbane held a substantial investment via convertible notes. The remaining investors were Schipol airport (Amsterdam) and various funds managed by private sector entities such as Prudential, ANZ and Norwich Union (UK). However, by 2006, neither the national government nor the City of Brisbane remained as major investors. The state government continues its involvement through the Queensland Investment Corporation with a 25% shareholding at 30 June 2013, and Schipol retained its stake, but otherwise there was a turnover of the institutional investors to Colonial First State, Commonwealth Bank Group Super, IFM Infrastructure Funds, Motor Trades Association of Australia, National Asset Management and Sunsuper Pty Limited (Brisbane Airport, 2014).

Similar to Sydney and Melbourne airports, Brisbane only pays low tax, although there was a substantial increase in 2010 over the previous years. Again, similar to Melbourne airport, the privatisation of Brisbane airport led to a prolonged 10-year interruption to income tax receipts for the national government. Brisbane airport paid tax in two of the three years 2011 to 2013.

The first GPFR produced after privatisation shows that the retained profit figure was $0; that is, Brisbane airport did not inherit a gain or a loss. Since then the company has had mixed results. In 2000 the company reported its worst post-privatisation loss of approximately $113m, largely due to one-off write offs of deferred borrowing costs. After that, performance tended to improve, although it remained patchy until 2004. Some of the dramatic changes in the retained profits are due to transfers of equity between accounts. For example, in 2003 the company transferred approximately $164m from retained earnings to general reserve. Financial performance has remained patchy, with substantial profits in 2011 and 2013 interrupted by a smaller loss in 2012.

In 2004 there was a change in corporate structure (see note 18 of the 2006 GPFR for Brisbane airport), which makes it impossible to reconcile movements in retained earnings for the period 2004-2006. Similar to Melbourne airport, Brisbane airport has recognised changes in the fair value of its investment properties in the income statement since 2005. This has had an aggregate impact (up to and including 2010) of $248m on the firm’s before-tax profits.

Brisbane airport has been able to generate positive operating cash flows. However, it is seeing an increase in the borrowing costs paid. The largest single component of its debt relates to redeemable preference shares, which carry an interest rate of 12% (down from 15% previously). At 2013, these instruments represented $480m out of $2,394m in interest bearing liabilities (approximately 20%).

Similar to Melbourne, Brisbane has been able to maintain and increase the size of its positive net assets. Part of this is due to $284m in revaluations of investment properties to 2010, with a further $220m in the three years to 2013, a total of $504m.

Due to the change in corporate structure of Brisbane airport, it is not possible to use changes in retained profits over the sample period to compare the performance of the three airports. However, we can gain some sense of their relative performances by adding the operating profit figure after tax (Figure 3) for the periods 2002-2010. This shows that Sydney airport’s aggregate performance equals negative $1,186m, while the corresponding figures for Melbourne and Brisbane are both positive at $819m and $391m respectively. For the period 2011-2013, corresponding figures are: Sydney +$287m; Melbourne +$575m; Brisbane +$277m.

Airport | 2002-2010 | 2011-2013 | 2002-2013 |

Sydney | -$1,186m | $287m | -$899m |

Melbourne | $819m | $575m | $1,394m |

Brisbane | $391m | $277m | $668m |

Figure 3. Operating Profit after Tax

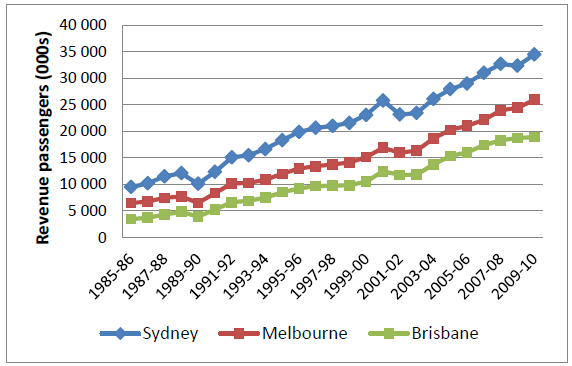

Sydney airport has almost twice as many passengers and aircraft movements as Brisbane airport. Similarly, Melbourne processes approximately three-quarters of the passengers and aircraft movements as Sydney. However, despite this substantial (though slowly eroding) advantage in customer base, Sydney’s performance is the weakest on all financial metrics presented.

The Productivity Commission (PC, 1998) showed that total tax receipts for all airports under the control of the FAC in 1997 were approximately $82m. If we make a simplifying assumption that 80% of this figure relates to the three airports considered in this study, this would imply Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane airports contributed approximately $64m in taxes in 1997. An analysis of the GPFR of these airports indicates that this figure was not surpassed again until 2009, when the combined income taxes paid by these airports totalled $71m.

This analysis does not lend itself to the conclusion that the private sector was able to liberate more wealth or run the airports more efficiently than the FAC. This particular privatisation exercise has seen an erosion of the income tax and dividend streams of government revenue. In addition, the figures for growth in passengers and aircraft movements do not indicate that privatisation has led to a freeing up of a bottle-neck in the operation of these assets. These airports have gone from being profitable under the FAC regime to weakly profitable at best and wealth destroyers at worst.

4. Service Quality

In assessing performance indicators for non-financial matters, this paper relies heavily on data publicly available from the ACCC, which has produced annual reports on key performance areas since airport divestment in 2002 as part of its role on behalf of government in light-handed monitoring of the privatised airports. These reports include indicators such as airport prices, parking, costs, profits and investment levels. The ACCC also uses a range of indicators to determine an overall rating of the airports' quality of service that includes the views of airlines, border agencies and passengers in relation to service quality. A proposed inquiry into economic regulation of airport services to be conducted by the Productivity Commission, was brought forward by the national government after the 2008–09 ACCC airport monitoring report, concerned in particular by the findings that Sydney airport had increased profits by “allowing service quality to fall below that which could be expected in a competitive environment” (ACCC, 2010: 17).

The ACCC points out, however, that “monitoring of itself does not restrict airports from using their monopoly position to increase prices and/or lower service standards. Importantly, monitoring does not directly restrict the airports from increasing process and/or lowering standards and does not provide the ACCC with a general power to intervene in the airports’ conduct in setting of terms and conditions for access” (ACCC 2014: xiii).

In its submission to the PC, the ACCC noted that its monitoring results indicate that, over several years (including the most recent year), the quality of service provided to airlines by Sydney Airport has remained less than satisfactory on average, while over the same period, the airport’s average prices and profitability for those services have continued to increase. In their survey responses, airlines have consistently identified Sydney Airport as the least responsive of the airports with respect to service delivery and quality over a sustained period of time. This lends support to the notion that airlines have been unable to negotiate an acceptable level of service with Sydney Airport, despite paying higher prices. The other airports were rated satisfactory by the airlines on average over the last five years (ACCC, 2011a).

Subsequently, the ACCC found that in 2012-13 Sydney airport had the highest aeronautical revenue per passenger ($15.53). By the 2012-13 year, the assessed standard of service was comparable to Melbourne, though not as good as Brisbane. The ACCC also commented that Sydney airport remained the airport with the least favourable combination of aeronautical prices and quality of service rating (ACCC, 2014: xxvii).

The ACCC found that while passengers were happier with international check-in times at Sydney, they felt kerbside congestion was worse, leading to an overall unchanged rating of “satisfactory”. Airlines’ rating, previously “poor”, declined further with comments about the lack of parking bays, the availability of taxi ways and the quality of aprons (ACCC, 2014: xiii). The ACCC reports that these results are worse than those from other airports and noted that over the same period, prices and the operating margin continued to rise (ACCC, 2014b: 14-15).

In an earlier report, the ACCC concluded that these results, when considered within the context of the airport’s market power as well as the incentives and ability to use that market power, point to Sydney airport earning monopoly rents from services provided to airlines (ACCC, 2011b: 44). The Chairman of the ACCC was reported as saying that “Sydney Airport has increased profits by permitting service quality to fall below that which the airlines reasonably expect. Airport users, including passengers and airlines, rated Sydney Airport last among the monitored airports for the fourth consecutive year” (Dorman, 2010b). Later, however, the ACCC stated that it did not have sufficient information to determine whether the airports were exercising their market power to extract monopoly rents (ACCC, 2014: 309).

Among the loudest complaints about the airports is the cost of parking, especially since privatisation, fuelling monopoly pricing accusations. The national government directed the ACCC to monitor car park prices at Australia's five big airports, including Melbourne and Sydney. The findings revealed that on average, 11% of the airports' revenue is from parking, with Melbourne yielding 21% and Sydney 7%. The ACCC has claimed that these findings are “consistent with airports having a monopoly position” and singled Melbourne out as a particular case of price gouging with respect to parking. What is clear is that prices are significantly higher than those charged in major overseas airports (Maunder,

2009), in Melbourne’s case, the average amount paid by each vehicle parked there almost doubled from $15.97 to $29.72 since privatisation (McIlwraith, 2011). Further, even Sydney’s mass transit option, the rail link, has a “station access fee” levied by the private operator of the rail section to the airport, making it a much more expensive trip in comparison with other regular rail charges in Sydney (McIlwraith, 2011). For 2012-13, the ACCC noted continuing increases (though generally small) in parking prices, and that the proportion of operating surplus from parking had stabilised in Sydney, increased in Brisbane, and reduced (from a very high level) in Melbourne (ACCC, 2014: 27).

In response to the ACCC, Sydney airport’s submission to the PC inquiry criticised the current monitoring model, stating it “fails to provide the information necessary to assist the airports and airlines to improve performance, lacks credibility in its assessment of the airports’ contribution to joint service quality, lacks transparency” (SACL, 2011: 86). The submission recommends improved, light-handed airport monitoring; it noted that “that, if done competently and professionally, quality of service reporting can be an important tool that enables airports and airlines to improve the performance of their joint service to passengers.” It suggested that future service quality reporting focuses on passengers only, to enable airlines and airports to understand where improvements need to be made. It argued that any service reporting regime should accurately inform air passengers and other stakeholders which organisations are responsible for delivering the services provided during each stage of their journey (SACL, 2011: 85).

Despite unflattering quality indicators, traffic volume indicators at the three airports show a rising trajectory (see Figure 4), partly explaining the increased profitability and suggesting that the monopoly position of each airport might be relevant. This issue of real or potential abuse of market position was raised during the initial debates on the privatisation legislation, with the then Minister responsible for Transport predicting that “the risk of anti-competitive behaviour by major airlines at any of the general aviation airports is very low” (Tuckey, 2002). After considering the evidence from the ACCC, the PC concluded that there was little evidence that airports had misused their market power (PC, 2011). However, it is also clear that the current monitoring arrangements will continue, clearly in an attempt to maintain checks on the potential abuse of market power in the future. The government department responsible for advising on matters such as airport monitoring has even suggested some broadening of the scope of the current monitoring and reporting regime (DIT, 2011: 1, 2).

With respect to monopoly, it needs to be noted that in relation to aeronautical charges, airports do compete for airline custom which is reflected in differing fee arrangements negotiated at airports for different airlines. Similarly, some of the retail services also face competition from other airports both nationally and internationally. However, the fundamental issue is that this competition is at the margins of airport activity and is unlikely to include competition for passenger custom given the geographical distances between airports.

In terms of overall service quality, after considering evidence from the ACCC, the PC reported that “on a rating scale ranging from very poor to excellent, the overall ratings of the airports were largely satisfactory” with Brisbane airport the only Australian privately-owned airport to achieve an overall rating of “good”. The PC reported that “quality of service ratings from airline surveys are notably lower [than those by passengers], including ratings of „below satisfactory’ for both Sydney and „satisfactory’ for Brisbane and Melbourne” (PC, 2011: 123). Sydney airport managed to lift its quality of service rating from poor to satisfactory for the first time since the consumer watchdog (ACCC) began monitoring the aviation industry 12 years before (Burke, 2012).

Figure 4. Passenger flows 1985-2010

Source: BITRE 2011 table T.6.4

5. Conclusions

The claims that Australia’s airports are able to generate efficiencies and improved performance that government owners cannot is a difficult argument to sustain, especially in light of the performance of Sydney airport. In Sydney’s case, weak financial results are taking place against a background of increasing traffic volume indicators that should make it easier for the airport to generate profits. At the time of divestment, the government also removed some of the regulatory controls which had applied to airport ownership and operations, by passing the Airports Amendment Bill 2002. The then Minister for Regional Services, Territories and Local Government argued that this bill would remove unnecessary restrictions on the operation of general aviation airports and increase the scope for investment in airport operator companies (Tuckey, 2002).

Sydney airport’s operating profit is 80% of operating revenue; each dollar it spends to run the operation earns $5, yet the net loss in 2009 was almost $150m (Dorman, 2010a) in an environment where the capacity to earn greater revenues has been improved since public ownership through lighter government regulation and improved passenger demand. MAp’s ability to create highly innovative transactions and corporate structures should be recognised as prodigious. However, whether this model is sustainable over the long haul has yet to be established. Christopher Dinn from consumer advocates Choice argues that “Sydney Airport would be out of business if it was a restaurant but it remains in business because it is a monopoly” (Dorman, 2010a).

Maintenance of the public interest is also a prime concern with any divestment of public assets. This might include the transfer of interest across time considering that future revenue streams will now accrue to the private sector from the sale of the public asset. Further, governments have traditionally had a difficult time understanding and forecasting the true value of their assets, given complex and uncertain future population, economic growth, travel patterns, and cash flows. Selling a public asset below its true value may capture definite windfalls in the near term, but may be a regrettable decision over the longer run.

The PC report did comment favourably on the increased levels of investment in aeronautical infrastructure since privatisation, and that airports have not experienced the bottlenecks that have beset other infrastructure areas (PC, 2012). This is consistent with the expectations expressed by the Howard government in terms of using market mechanisms to generate further private investment in infrastructure generally, and airports in particular. It does raise the issue of whether or not the government would have been prepared to invest as heavily in airports or whether the government owners would have been able or willing to make as much economic use of the limited land at airports as have the private owners.

The PC report commented unfavourably on access to airport precincts arguing that it was because of inadequate arterial roads and insufficient mass transit services. However, this criticism is clearly not directed at the airports themselves, but it does reflect the need for a coordinated approach to broader transport issues when assets such as these are privatised. There are important public interest dimensions of airports that still require government intervention: establishing a robust regulatory regime is one, and ensuring the integration of transport systems is another.

The question still arises, if organisations under private ownership are not intrinsically more efficient than those under public ownership, why has there been such a focus in many jurisdictions on ownership change through privatisation? This resonates in the case of privatised airports, especially when there is a need for government regulation to prevent misuse of market power.

This analysis of the effectiveness of airport performance under private ownership raises considerable skepticism regarding blanket claims that the private sector is much more effective than the public sector at liberating wealth from infrastructure assets. The former Prime Minister, John Howard, promoted the view that “there are good economic reasons for those airports to be operated by private industry” and that “the experience all around the world has been that privatised airports get run better” (Howard, 2002). In light of recent airport performance, it is difficult to justify a view that governments should always prefer private sector organisations to deliver public services and that the option of a GBE might also be considered against private ownership.

The private sector should not be presumed to act in the public interest; clearly their primary accountability is to their shareholders. This means that governments are primarily responsible to ensure that the public interest is considered when determining any given asset divestment (or in the case of other forms of privatisation). The need to factor in “publicness” (Aulich, 2011) has not always been accepted by recent conservative governments in Australia and there have been cases where public assets have been divested and the public has either not been sufficiently well compensated from the sale or sufficiently protected after the sale where weak regulatory arrangements have been adopted. It appears that this problem has emerged more often in relation to the divestment of public monopolies, such as the Australian Wheat Board (see, for example, Botterill, 2012). This contrasts markedly with the post-privatisation protections offered in other industries that were privatised in Australia, particularly those operating in contestable environments such as banking, insurance or airlines where the government liberalised entry arrangements to enable international providers to compete with the former government-owned enterprises.

While the airport environment is less contestable, it needs to be noted that the regulatory regime established by the Australian government has been important in enhancing the accountability of the new airport owners for their management. The on-going annual monitoring conducted by the ACCC has proven significant in keeping a focus on performance standards and alerting the public and government to areas and functions where performance standards have been problematic. The full evaluation of the service quality conducted by the PC can be directly related to the public reporting of lower standards by the ACCC. These mechanisms, albeit light-handed, have been successful in holding the new owners to account. The PC has recognised that the largest airports do possess significant market power but has concluded that aeronautical charges do not point to the inappropriate exercise of that market power (PC, 2012). Nevertheless, persistent claims remain of abuse of market power in relation to non-aeronautical services, such as parking, as do concerns about the overall level of service delivery, especially aeronautical services.

The mode of privatisation needs to be carefully considered in future arrangements to divest major transport facilities. The blending of high finance and transport operations that Macquarie specialises in is especially complex and perhaps, under some circumstances, may be especially risky from both a shareholder and citizen’s perspective. The model of public-private ownership mix that operates at Melbourne and Brisbane appears to be less risky and may contribute to their better performance; nevertheless, it is likely that performance differences relate to the management model more than to ownership arrangements.